Adaptive exponent for Adam

One long-standing issue preventing the complete adoption of adaptive optimization methods for training neural networks is the generalization gap between adaptive optimization methods and stochastic gradient descent with momentum (SGDM). Using adaptive methods, such as Adaptive Moment Estimation (Adam) which I will introduce later, with default values or with slight tuning usually yields good performance. This may sometimes be good enough, and at the very least serves as a useful baseline. However, the performance of adaptive methods on validation or test sets especially with regards to image data is often somewhat worse than can be achieved with SGDM. This is clearly reflected in the top papers pushing the state-of-the-art image classification error for imagenet, where SGDM is almost universally used. An important objective is to close the generalization gap between adaptive methods and SGDM, thus reducing the amount of effort spent tuning, capturing the typical quick initial learning of adaptive methods and at the same time squeezing the most performance out of the architecture in question.

Adam is the most popular adaptive optimization method and is the latest extension of Adagrad, an adaptive optimizer first introduced by Google in 2011. Interestingly enough, Adam was first published in 2014, and there has been no obvious successor since. In comparison, we’ve seen Resnet, Wide Resnet, Densenet, Mobilenet etc. series of novel neural network architectures in those same last 5 years.

To motivate Adam, I first introduce the update rule of Adagrad below, where g is the current gradient with respect to a particular weight.

where,

The intuition behind the v term is to accumulate values such that weights which are rarely updated are updated with a larger value when they do receive an update, and weights which are frequently updated are updated with a smaller value. A natural question may be why take the square root of v in the update? As it turns out, taking the square root of v works better empirically and this question will be revisited later. Another natural question may be why accumulate squared gradients? I’ve empirically tested accumulating values using abs(g) or counters with VGG-16 and ResNet-20 on the cifar datasets and the performance is worse. This is due to a theoretical motivation for accumulating squared gradients. v is an empirical approximation of the diagonal of the Fisher information matrix, and Fisher information can be understood as providing local curvature information.

Are we done? Well, v appears to grow monotonically and what happens if we add momentum? We arrive at Adam. Adam maintains a running exponential average for v to prevent v from growing indefinitely and also incorporates a momentum term. The formula is given below, omitting a correction term for simplicity.

where,

To ensure v has a relatively long memory, is often 0.999. A typical

value is 0.9.

The question revisited here is why take the exponent of v to be 0.5? What happens if we take the exponent of v to be 0? Observe that,

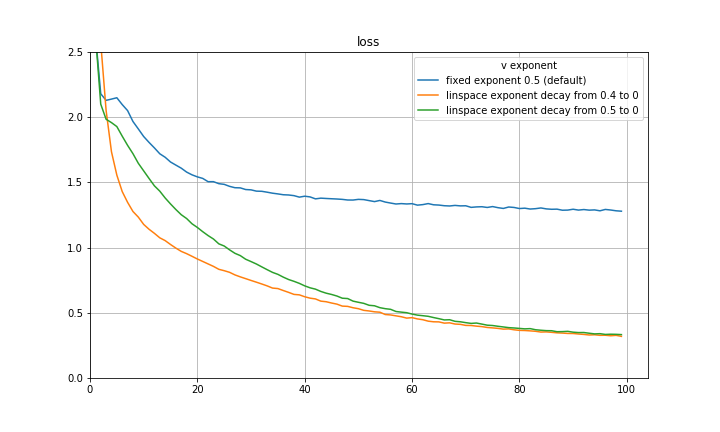

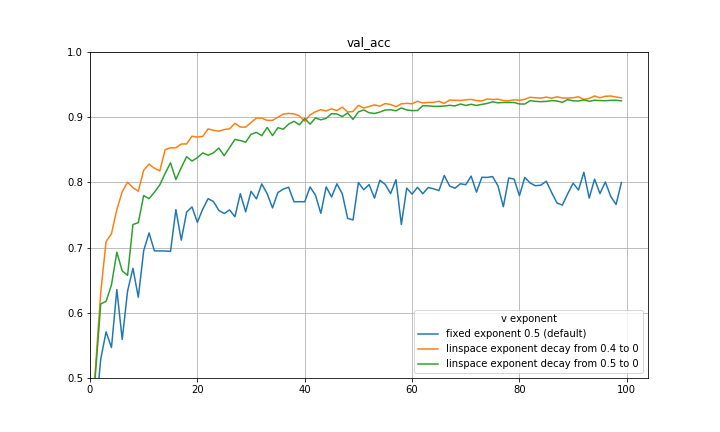

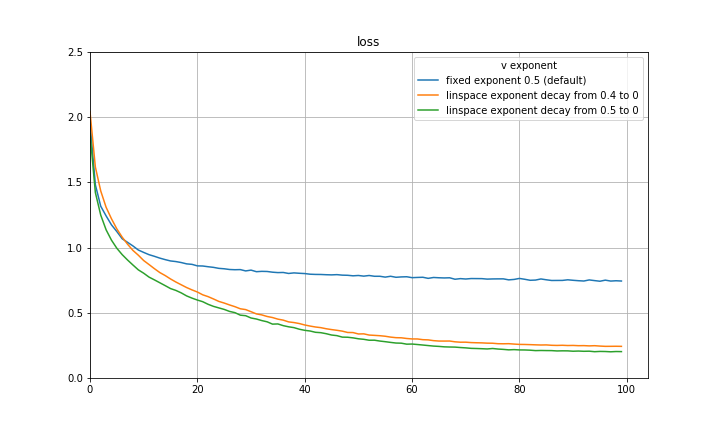

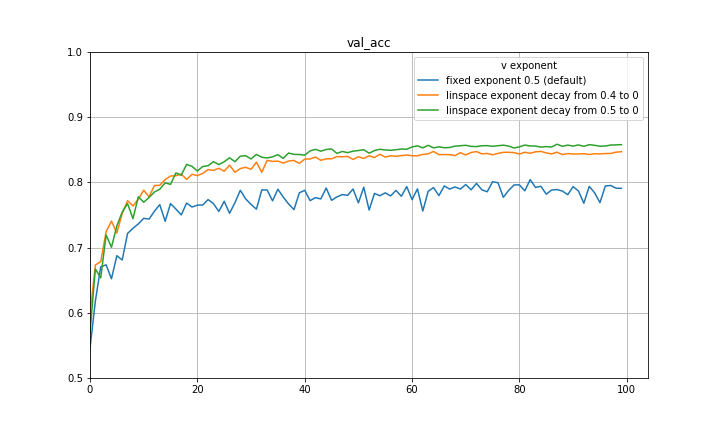

and setting the eta and beta accordingly recovers SGDM! I think a natural way to capture both the initial quick learning of Adam as well as the generalization of SGDM is to begin with an exponent of 0.5 and decay to some smaller exponent such as 0 using some decay rule. Below are some preliminary experiments on CIFAR-10 using a VGG-16 architecture, disregarding learning rate decay, and decaying the exponent at a constant rate. There are significant improvements in both loss and validation accuracy. It is quite possible that a part of the improvement can be attributed to the exponent decay mimicking learning rate decay, however the results are still substantial.

The experiments are repeated with a ResNet-20 architecture and findings are similar.

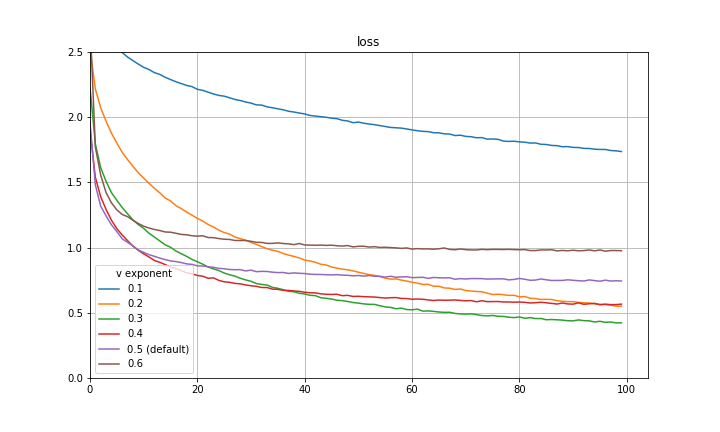

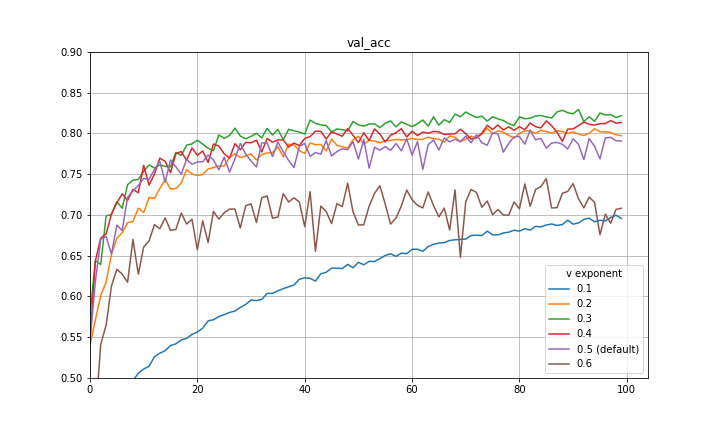

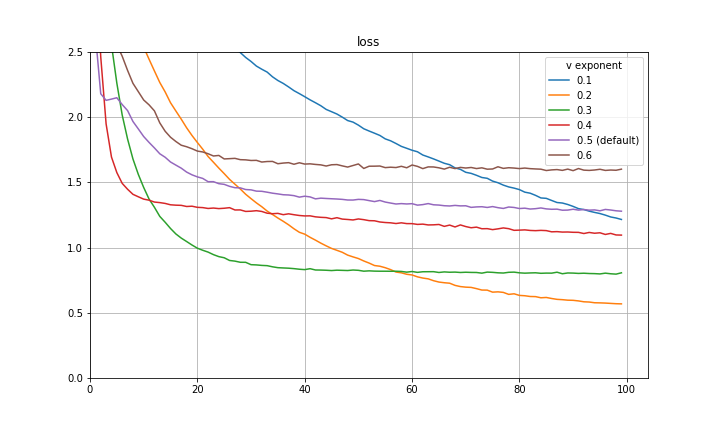

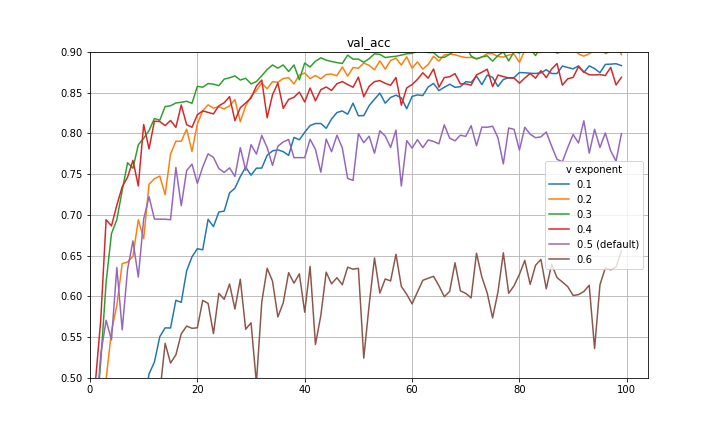

I make a final note here that there is a great paper by Quanquan Gu, a professor at UCLA, named Closing the Generalization Gap of Adaptive Gradient Methods in Training Deep Neural Networks which proposes to use a fixed exponent of v between 0 and 0.5. This is also certainly a good approach and empirically closes some of the generalization gap between Adam and SGDM. Included below are some more preliminary experiments with fixed exponent of v between 0 and 0.5 for CIFAR-10 and a VGG-16 architecture. It is clear that for the particular hyperparameters in use, 0.5 is not the optimal exponent of v. This is also evidence that the improvement achieved with the decay of the exponent is not purely mimicking learning rate decay.

The experiments are repeated with a ResNet-20 architecture and findings are similar.